Shared by Julia Silverberg Nemeth

In the 1970s and 1980s, Julia Silverberg Nemeth’s childhood wasn’t like many others. Her parents and grandmother, who lived with them, built a homestead in the woods of northern Minnesota 20 miles outside of a town called Park Rapids. The family foraged for mushrooms to mix into a hunter’s stew and her mother Edith stuffed kohlrabi and simmered the root vegetable in a Hungarian sour cream and dill sauce. On Fridays, her grandmother Juliana made golden chicken soup with farina dumplings called galushka and the family fried doughnuts filled with apricot jam that they called fánk in December. “I didn’t know I was Jewish, but we were eating chicken soup every Friday,” Julia says. “I thought that was maybe a Hungarian tradition.”

When Julia was 20, her mother said she had something important to share with her. Overwhelmed by tears and fear, she never revealed her secret and passed away shortly after. Looking back, Julia writes, “I know without a doubt that my mother was going to tell me we are Jewish. She wanted me to help her find a way back from her secrets.”

Born in 1896, as an ethnic Hungarian of Israelite descent, Julia says, her grandmother Juliana lived outside of Cluj-Napoca in Transylvania and worked as a hairstylist, owning her own salon, a rarity for women at the time. Her grandmother gained fame and was invited to do the hair of the queen of Romania, Marie, at her home near the Black Sea. In 1925, she gave birth to Edith and in the 1940s, they left Transylvania for Budapest. It’s “very lucky they did so because all their relatives who stayed behind... were sent to Auschwitz and died,” Julia shares.

They found a small reprieve in Budapest for a time. But, in 1944 during a bombing raid, Edith was turned away from two shelters because of her yellow star, which declared she was Jewish. Amidst mortar shells, she ripped it off. “This was a crime that was punishable by death,” Julia explains. “But my mother's choices seemed to be death by bombs or death because of her crime. She chose to try to survive the crisis at hand.” Passing as a gentile, she was allowed into a shelter.

Later that year, Edith was forced to march the 150 miles to Vienna and was sent to Bergen-Belsen while her mother remained in the Budapest ghetto near the Dohány Synagogue. Everytime authorities came, “she would just lay on the ground and pretend [to be] dead…. She said she felt she had survived by this ruse,” Julia explains.

Edith, who contracted typhus, nearly didn’t make it back to Budapest after the war. “Hardly anyone came home, but my Editke came home,” Julia’s grandmother would later tell her. In 1964, the family left for the U.S. as refugees.

“When they came to America, they decided not to tell anyone they were Jewish, including me,” Julia explains.

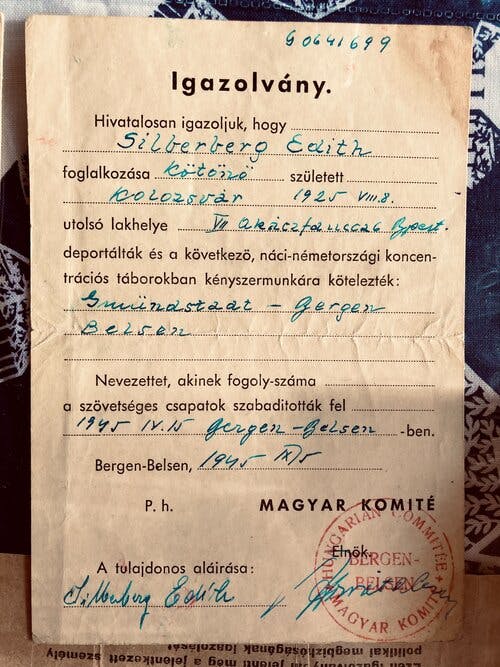

Missing the scent of her mother after she died, Julia went to her dresser to find her hairbrush. Under it, she found a small yellowed envelope. “It really felt like she’d left it there for me,” she explains. In it, Julia found her mother’s liberation papers from Bergen-Belsen and other documents that showed she was Jewish.

The papers felt like a liberation to Julia too, from the secrets and fears she felt growing up. It set her on a path to explore her family’s history at Holocaust museums and in Central Europe. “I’ve been everywhere putting together this puzzle,” she explains.

She’s also thought a great deal about the moment her mother ripped off her yellow star, considering how safe she must have felt to pass as a gentile and that she wanted that feeling for her children. Symbolically, though, Julia writes, “I see myself picking up the yellow star she cast away and saying to my mother, ‘It's ok, mama, I can take this over now.’”

She has, celebrating her Jewish heritage through holidays and Shabbat dinner with her own daughter Zsófia and by preparing the family recipes like the chicken soup and the fánk for Hanukkah. The food, she adds, is proof her family survived.